Iranian Festivals and Celebrations: A Guide to Persian Traditions

Iranian Festivals: Timeless Traditions Celebrated Globally

Iran’s festivals and celebrations offer an incredible glimpse into Persian culture and heritage. From Nowruz, the Persian New Year, to Yalda Night, these traditions reflect centuries-old customs and rituals. Each event provides visitors with a unique opportunity to connect with locals, enjoy authentic cuisine, and witness traditional performances. Whether you’re exploring ancient Zoroastrian festivals or experiencing modern celebrations, these events highlight Iran’s rich cultural landscape. Planning your trip around these dates ensures a memorable experience filled with cultural significance.

Discover more about these festivals and their role in Iranian life with this comprehensive guide to Persian traditions.

Iranian Festivals and Celebrations

“When the rose garden fades, the nightingale still sings of spring.” This timeless line from Saadi, one of Persia’s greatest poets, captures the essence of Iranian festivals—a celebration of nature, renewal, and the eternal spirit of unity. For millennia, these festivals have marked the rhythm of life, offering Iranians a chance to honor their history, commune with their gods, and revel in the beauty of their land.

Iranian festivals are more than rituals; they are a living chronicle of a civilization that has stood the test of time. From the grandeur of Nowruz, the Persian New Year that heralds spring’s arrival, to the solemn observances of Ashura, these celebrations weave together the spiritual, natural, and communal aspects of Iranian identity. Many of these festivals, such as Nowruz and Yalda Night, are now inscribed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage, symbolizing their global and historical significance.

The Ancient Roots of Persian Celebrations

The origins of Iranian festivals are deeply intertwined with Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions. In ancient Persia, festivals were a way to honor Ahura Mazda, the supreme god, and to celebrate the elements—fire, water, earth, and air—that sustain life. Each festival carried profound meanings, connecting humanity with the divine and nature.

Gahanbars, the six Zoroastrian seasonal festivals, marked pivotal moments in creation, such as the birth of the sky, water, earth, and humans. These celebrations emphasized gratitude and charity, teaching that joy and prosperity come from unity and selflessness.

Festivals as a Cultural Bridge

Iranian festivals have evolved over centuries, reflecting the history and traditions of Persian civilization. During the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), events like Nowruz became state celebrations, fostering unity among the empire’s diverse communities. These traditions continued through the Sasanian era and adapted under Islamic influence, merging pre-Islamic and Islamic customs seamlessly.

Festivals such as Mehregan, honoring love and friendship, and Tirgan, celebrating the legendary tale of Arash the Archer, emphasize Iran’s deep connection to human values and natural cycles. Today, these events link Iranians to their ancestral roots and offer insights into the nation’s cultural legacy.

Nowruz: Iran’s Global Celebration

Nowruz: The Iranian New Year

O nightingale, sing your ode to spring, for the garden awakens from its slumber.” These evocative words from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh capture the essence of Nowruz, the most cherished celebration in Iranian culture. Heralding the arrival of spring and marking the beginning of the Iranian calendar year, Nowruz is a profound blend of history, spirituality, and joy, celebrated not only in Iran but across the globe.

Origins and Zoroastrian Influence

Nowruz, meaning “New Day,” has roots stretching back over 3,000 years to Zoroastrianism, the ancient Persian faith. It was originally a tribute to Ahura Mazda and a celebration of light’s triumph over darkness. Coinciding with the vernal equinox, this festival symbolizes the rejuvenation of nature and the cosmic balance between good and evil.

The Achaemenid kings institutionalized Nowruz as a national holiday, marked by feasts, gifts, and grand ceremonies. Persepolis, the ceremonial capital, hosted Nowruz celebrations where delegations from across the empire presented their tributes. This tradition underscored Nowruz as a unifying event, embodying harmony and renewal.

Symbolism and Elements of the Haft-Seen Table

The centerpiece of Nowruz celebrations is the Haft-Seen table, a beautifully curated arrangement of seven symbolic items, each beginning with the Persian letter “S.” These items represent life’s blessings and virtues:

- Sabzeh (sprouted wheat or lentils): Symbol of rebirth and growth.

- Samanu (sweet wheat pudding): Representing strength and patience.

- Senjed (dried oleaster): Evoking love and wisdom.

- Seer (garlic): A protector against evil and illness.

- Seeb (apple): Denoting beauty and health.

- Somāq (sumac): A reminder of the sunrise and the spice of life.

- Serkeh (vinegar): Reflecting patience and acceptance of life’s hardships.

Additionally, the table often features a mirror symbolizing self-reflection, a goldfish representing life, and decorated eggs to signify fertility. Candles, representing light and hope, complete this tableau of renewal.

Modern-Day Global Recognition and Festivities

Today, Nowruz transcends Iran’s borders, celebrated by millions in countries such as Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Azerbaijan, as well as among Persian communities worldwide. In 2010, Nowruz was added to UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage, affirming its global cultural significance.

Modern celebrations retain their ancient essence while incorporating contemporary touches. Families engage in spring cleaning, symbolizing a fresh start, and don new clothes to welcome the year with optimism. Visits to loved ones, known as Eid Didani, are accompanied by gift exchanges and the sharing of special dishes such as Sabzi Polo ba Mahi (herbed rice with fish).

The 13-day festivities culminate in Sizdah Bedar, a joyful day spent outdoors. On this day, families picnic in nature, symbolically casting away the year’s misfortunes by discarding their Sabzeh into flowing water.

Mehregan: The Festival of Friendship and Gratitude

“Let us cherish love and kindness, for they are the bonds that hold us together.” This sentiment lies at the heart of Mehregan, an ancient Persian festival dedicated to Mehr—the divine representation of love, friendship, and light. Celebrated every year on the 16th day of Mehr in the Persian calendar (mid-October), Mehregan is a vibrant expression of gratitude, unity, and communal joy.

Historical Significance and Connection to Mithraism

The origins of Mehregan trace back thousands of years to Mithraism, an ancient Persian religion that predates Zoroastrianism. Mithra, the deity of light, justice, and covenant, was central to Persian spirituality. The festival honored Mithra as the guardian of truth and harmony, embodying the values of love and friendship.

In Zoroastrian tradition, Mehregan evolved to celebrate Mehr (compassion and loyalty) as one of the divine emanations of Ahura Mazda. The festival symbolized the cosmic balance and human dedication to truth and kindness.

Historically, Mehregan was as significant as Nowruz, with elaborate court celebrations during the Achaemenid and Sasanian periods. It marked the autumn harvest, a time of abundance and thanksgiving. According to Persian mythology, Mehregan commemorates Kaveh the Blacksmith and the people’s revolt against Zahhak the Tyrant, symbolizing the triumph of justice and unity.

Cultural Expressions and Festive Traditions

The festive spirit of Mehregan manifests in vibrant customs that have endured across centuries.

Preparations and Decor: In preparation, households are cleaned, and families decorate their homes with seasonal flowers, particularly marigolds and lotuses. Tables are adorned with purple or gold cloths, symbolizing royalty and light. Items such as fruits, nuts, and pomegranates are arranged alongside a mirror, candles, and incense, creating a symbolic altar.

Prayers and Rituals: The celebration begins with prayers to Ahura Mazda, invoking blessings for prosperity and happiness. A bowl of rose water and sprigs of basil are used for purification, symbolizing the renewal of spirit.

Communal Feasts and Gratitude: Central to Mehregan are the shared feasts that bring families and communities together. Traditional dishes like ash-e reshteh (a hearty noodle soup) and rice with saffron reflect the harvest’s bounty. Participants exchange gifts and share tales of kindness and bravery, reinforcing the festival’s emphasis on human bonds.

Cultural Performances: Music and dance enliven the festivities, with traditional storytelling often recounting the triumph of light over darkness, such as the legend of Kaveh and Zahhak. These performances instill a sense of pride in cultural heritage.

Global Celebrations: Today, Mehregan is celebrated by Zoroastrians and Persian communities worldwide, particularly in Iran, India, and the diaspora. While its ancient roots remain central, modern observances often integrate contemporary elements, such as poetry readings and environmental awareness campaigns.

Yalda Night: The Victory of Light Over Darkness

Arise, for the longest night must yield to the dawn.These poetic words, often recited on Yalda Night, epitomize the significance of this ancient Persian festival. Celebrated on the winter solstice, Yalda marks the longest night of the year, symbolizing the triumph of light over darkness and the renewal of hope.

Astronomical Relevance and Mythology

Yalda Night falls on December 21st or 22nd, the winter solstice, when the night is at its longest and the day at its shortest. This celestial event has deep significance in Persian cosmology, representing a pivotal moment when the sun, a symbol of light and life, begins its gradual return to prominence.

The festival’s name, Yalda, means “birth” in Syriac, alluding to the rebirth of the sun. In Zoroastrian cosmology, this night was viewed as a battle between the forces of good (light) and evil (darkness). As the night reaches its zenith, Mithra, the deity of light, emerges victorious, heralding the sun’s revival and the promise of longer days.

This duality of light and darkness reflects broader Persian philosophy, emphasizing resilience, renewal, and the inevitable triumph of goodness. Ancient Iranians believed that spending this night in the company of loved ones could shield them from the negative forces associated with long darkness.

Modern Customs: Family Gatherings, Poetry, and Traditional Dishes

Yalda remains one of the most beloved celebrations in Iran, with customs that bring families together in joy and reflection.

Family Gatherings: On Yalda Night, families gather, often in the homes of their eldest members, to share warmth and laughter. These gatherings extend late into the night, symbolizing solidarity in the face of darkness. The living room becomes the heart of the celebration, illuminated with candles and decorated with colorful spreads of fruits and sweets.

Poetry and Storytelling: The literary soul of Iran shines on Yalda, with poetry readings forming an essential part of the celebration. Families recite verses from Hafez, Iran’s beloved poet, seeking his guidance through fal-e Hafez, a divination ritual using his poetry. Similarly, tales from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh recount the epic struggles of good and evil, mirroring the symbolic essence of the night.

Traditional Dishes: The Yalda feast is a vibrant tableau of seasonal offerings. Two fruits take center stage:

- Pomegranates: Their ruby-red seeds symbolize the glow of dawn and the cycle of life.

- Watermelon: Representing the warmth of summer, it is believed to protect against the harshness of winter.

Other traditional dishes include ajil-e shab-e yalda (a mix of nuts and dried fruits) and warm treats like kadoo halva (pumpkin dessert). The shared meal reflects abundance, gratitude, and the enduring spirit of hospitality.

Yalda Night is more than an astronomical phenomenon; it is a celebration of the human spirit’s resilience against the challenges of life. Its customs—rooted in unity, storytelling, and the natural cycles of light and darkness—continue to resonate deeply with Iranians and Persian communities worldwide. In gathering together, sharing poems, and embracing the longest night, Yalda reminds us that even in the darkest moments, light and renewal are just beyond the horizon.

Chaharshanbe Suri

With the leap over the fire, let my yellowness go and my redness stay. This heartfelt chant echoes the essence of Chaharshanbe Suri, the Persian Festival of Fire. Held on the eve of the last Wednesday before Nowruz, Chaharshanbe Suri is a jubilant celebration that blends ancient Zoroastrian traditions with modern communal joy, marking the transition from winter’s dormancy to spring’s vitality.

Symbolism of Fire and Purification

Fire, in Persian culture, is a powerful symbol of purity, light, and life. In Zoroastrianism, fire is sacred, representing Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity, and the eternal fight against darkness. Chaharshanbe Suri’s central ritual, jumping over bonfires, is a testament to this reverence. Participants chant the phrase: “Zardi-ye man az to, sorkhi-ye to az man” (“Let my sickness be yours, and your redness be mine”).

This act is not merely symbolic; it reflects a spiritual cleansing, casting away negative energy, illness, and misfortune while absorbing the fire’s strength, vitality, and warmth. In essence, the flames serve as a bridge between the past’s burdens and the future’s renewal.

Origins and Transformation into a Communal Celebration

The origins of Chaharshanbe Suri date back to pre-Islamic Persia, rooted in Zoroastrian rituals that honored fire as a purifier. In ancient times, it was believed that spirits of the dead visited their homes during the last days of the year. To guide and honor them, families lit fires on rooftops or courtyards, symbolizing both illumination and protection.

Over centuries, as Islam integrated with Persian culture, the festival evolved, blending Islamic and Zoroastrian elements while retaining its core symbolism. The name Chaharshanbe Suri, meaning “Red Wednesday,” likely refers to the fiery glow of the bonfires.

In modern times, Chaharshanbe Suri has transformed into a lively communal celebration. Bonfires illuminate city streets, courtyards, and parks as families and neighbors come together to celebrate. Traditional music, dance, and games create a festive atmosphere, with children often playing tricks in the spirit of Ajil-e Moshkel Gosha, or “problem-solving trail mix,” a symbolic offering of mixed nuts and fruits.

Customs Beyond the Flames

Beyond the bonfires, other customs enhance the celebratory spirit:

- Ghashogh Zani: Similar to Halloween’s trick-or-treating, children go door-to-door, disguised and tapping spoons on bowls to receive snacks.

- Fortune Telling: Families consult divinations, much like on Yalda Night, seeking guidance for the year ahead.

- Special Foods: Delicacies like ash-e reshteh (herbed noodle soup) and sweet treats reflect the abundance of the season.

Zoroastrian Gahanbar Festivals

The Gahanbars are six pivotal seasonal festivals celebrated by Zoroastrians, each marking a critical stage in Ahura Mazda’s creation. These ancient ceremonies emphasize gratitude for the natural world and unity within the community.

The Six Stages of Creation

Each Gahanbar corresponds to a specific creation event:

- Maidyozarem (Mid-Spring): Celebrates the creation of the sky.

- Maidyoshema (Mid-Summer): Honors the creation of water.

- Paitishem (Harvest): Dedicated to the earth’s fertility.

- Ayathrem (Autumn): Marks the creation of plants.

- Maidyarem (Mid-Winter): Commemorates the birth of animals.

- Hamaspathmaidyem (Year-End): Celebrates humanity and the renewal of life.

These festivals traditionally last five days, with the final day being the most significant.

Rituals, Community Spirit, and Shared Meals

Gahanbars are characterized by a profound sense of community and generosity:

- Rituals and Prayers: Celebrations begin with prayers and hymns, often recited in fire temples, to honor Ahura Mazda and the divine elements.

- Shared Feasts: Central to the Gahanbars is the preparation and sharing of meals. Everyone contributes, symbolizing equality and mutual support.

- Charity and Gratitude: Acts of kindness, such as feeding the less fortunate, reflect the festivals’ focus on righteousness and communal harmony.

The Gahanbars embody the Zoroastrian ideals of Asha (truth and order) and Vohu Manah (good intentions), reinforcing the connection between humanity and nature.

Monthly Zoroastrian Festivals

In addition to the Gahanbars, Zoroastrians observe monthly festivals that honor specific divine entities (Yazatas) or elements of creation.

Farvardegan (Festival for the Departed)

Held in the month of Farvardin, this festival is a time to honor the spirits of ancestors. Families visit cemeteries, clean graves, and light candles and incense, symbolizing the eternal connection between the living and the departed.

Ardibeheshtgan

Celebrated in Ardibehesht, this festival is dedicated to fire, the purest element in Zoroastrianism, and the flourishing of spring blooms. People gather to light fires, don white attire, and revel in music and dance amid nature.

Khordadgan

This festival in Khordad pays tribute to water, a source of life. Participants visit rivers and springs to cleanse themselves and recite prayers. Activities often include planting seeds and building irrigation channels, symbolizing renewal and sustainability.

Tiregan

Held in Tir, this festival celebrates Arash the Archer, who defined the Iranian-Turanian border by shooting an arrow across the land. Tirgan also honors Tishtar, the rain-bringing deity. Customs include water splashing, symbolic of rain’s blessings, and fortune-telling rituals.

Amordadgan

Observed in Amordad, this festival venerates nature’s vitality and abundance. Families spend the day outdoors, celebrating with food and festivities while emphasizing environmental preservation.

Shahrivaragan

Dedicated to Shahrivar, the Yazata of strength and wealth, this festival in Shahrivar honors the divine protection of resources like metals and minerals. Traditions include lighting fires, decorating homes, and sharing food with the underprivileged.

Abanegan

Held in Aban, this festival celebrates Anahita, the goddess of waters. Devotees gather near rivers and springs to recite hymns, light candles, and offer floral tributes, expressing gratitude for water’s life-giving properties.

Azargan

This fiery celebration in Azar reveres Atar, the Yazata of fire. Communities visit fire temples to offer prayers and light sacred flames, symbolizing illumination and warmth in the darker months.

Shiite Religious Observances

Islamic traditions hold a special place in Iran, particularly those reflecting Shiite values and beliefs, which are central to the country’s cultural and religious identity. Among the most significant Islamic celebrations observed in Iran are Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Ghadir, and Eid al-Adha, each carrying profound spiritual and communal importance.

Eid al-Fitr (Eide Fetr)

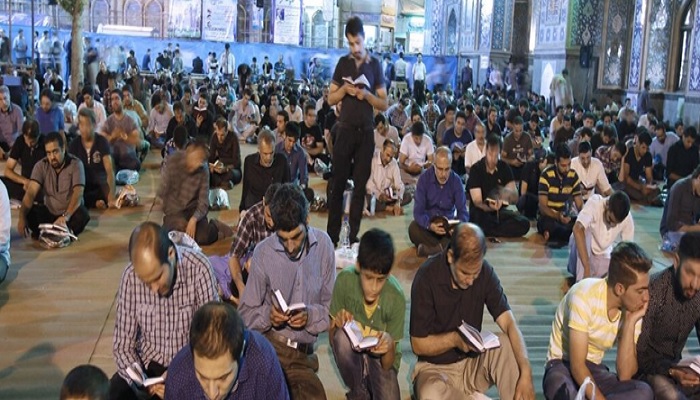

Eid al-Fitr, celebrated at the end of Ramadan, the holy month of fasting, marks a time of spiritual renewal, charity, and joy. It is one of the most widely observed festivals in the Islamic calendar, bringing communities together in gratitude and celebration.

Key Rituals and Customs:

- Special Prayers: Festivities begin with congregational prayers at mosques or open spaces, where the faithful express gratitude for the strength to complete Ramadan’s fast.

- Zakat al-Fitr: Acts of charity, or Zakat al-Fitr, are an essential aspect of Eid. Families donate food or money to the underprivileged, ensuring everyone can partake in the festivities.

- Family Gatherings: After prayers, families share elaborate meals featuring traditional dishes and sweets. Children often receive gifts or money, adding to the joyous spirit.

- Community Bonding: In Iran, people visit relatives and neighbors to strengthen bonds and share the joy of Eid.

Eid al-Ghadir

Eid al-Ghadir holds special significance in Shiite Islam. It commemorates the event at Ghadir Khumm, where Prophet Muhammad is believed to have appointed Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor. This event is seen as pivotal for Shiites, affirming their belief in the Imamate as central to Islamic leadership.

Key Observances:

- Ceremonial Gatherings: Shiite communities hold sermons and lectures that recount the events of Ghadir Khumm, emphasizing loyalty to Ali and his descendants.

- Expressions of Devotion: Devotees recite prayers and poems praising Ali, the first Imam. Homes and mosques are often decorated with banners and lights.

- Acts of Kindness: Sharing food, giving gifts, and performing charitable acts are integral to Eid al-Ghadir celebrations.

- Public Celebrations: In Iran, the day is marked by vibrant street processions, cultural events, and communal feasts.

Eid al-Adha (Eid-e Qurban)

Known as the Festival of Sacrifice, Eid al-Adha commemorates Prophet Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son in obedience to God’s command—a trial that ultimately reaffirmed his faith. In Iran, as elsewhere in the Islamic world, Eid al-Adha is a time of devotion, reflection, and charity.

Traditional Practices:

- Sacrificial Ritual: Families that can afford it perform the ritual slaughter of a lamb, goat, or cow. The meat is divided into three parts: one for the family, one for relatives and friends, and one for the less fortunate.

- Communal Prayers: Like Eid al-Fitr, the day begins with congregational prayers, emphasizing submission to God’s will and gratitude for His blessings.

- Feasts and Festivities: Families come together to enjoy festive meals, often featuring the sacrificial meat. Traditional Iranian dishes like kebabs and ash-e reshteh are commonly prepared.

- Acts of Generosity: Many Iranians use this occasion to support charitable organizations, reflecting the festival’s core principle of compassion.

Regional Celebrations in Iran

Iran’s cultural diversity is a defining feature of its identity, with each region adding unique traditions to the nation’s festive calendar. From the Kurdish highlands to the shores of the Caspian, regional celebrations showcase the rich heritage of Iran’s ethnic groups and their deep connection to their land, history, and faith.

Kurdish New Year and Yazidi Cultural Festivals

Kurdish New Year (Nowruz)

For the Kurdish people, Nowruz is not just the arrival of spring but a powerful symbol of freedom and resilience. Kurdish legends link Nowruz to the heroic tale of Kaveh the Blacksmith, who led a revolt against the tyrant Zahhak, marking the dawn of a new era.

Customs and Traditions:

- Fire Ceremonies: In the Kurdish regions, bonfires are lit on hilltops, symbolizing resistance and hope. Families and communities gather around the flames to celebrate unity.

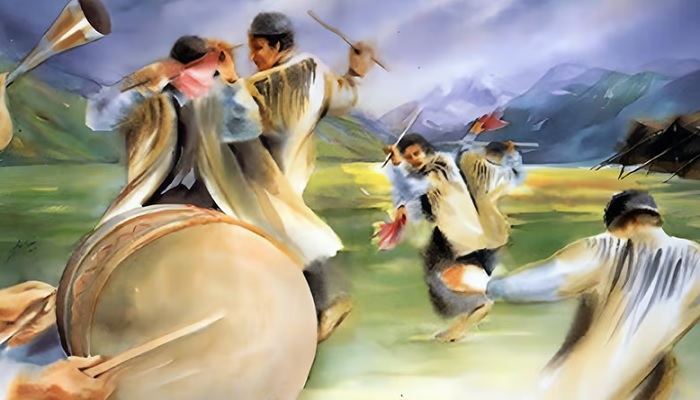

- Dances and Music: Traditional Kurdish dances, known as halparke, are performed in colorful attire, accompanied by the rhythmic beats of the daf and the melancholic melodies of the tanbur.

- Festive Foods: Kurdish dishes like kebab-e torsh (sour kebab) and dolma (stuffed vegetables) are staples of the Nowruz feast.

Yazidi Cultural Festivals

Yazidis, an ethno-religious group with roots in ancient Mesopotamia, celebrate festivals like Cejna Êzî (Feast of Ezid) and Sere Sal (Yazidi New Year), which reflect their reverence for nature and light.

Sere Sal is marked by:

- Egg Dyeing: Symbolizing fertility and renewal, dyed eggs are exchanged among family members.

- Pilgrimages: Yazidis often visit their sacred sites, such as Lalish, to offer prayers and perform rituals.

These festivals are not only spiritual occasions but also vibrant expressions of Yazidi identity and resilience.

Traditions in Baluchistan and the Caspian Region

Baluchistan

The southeastern region of Baluchistan is known for its tribal customs and festivals that celebrate the natural cycles of life and agriculture. Key traditions include:

- Ritual Dances: During weddings and seasonal festivals, Baluch tribes perform dances like the lewa, accompanied by the soulful sounds of the sorna (flute) and dohol (drum).

- Harvest Festivals: Seasonal celebrations such as Shadivary, which marks the harvest, are filled with communal feasting and storytelling.

Caspian Region

The lush, verdant provinces along the Caspian Sea—Mazandaran and Gilan—have their own distinct traditions:

- Tirgan Celebrations: Celebrated in villages near the Caspian, Tirgan is marked by water fights and the weaving of colored wristbands, which are later cast into rivers for good luck.

- Gilaki Festivals: Local Gilaki celebrations often feature rice harvest rituals, where families gather to thank nature for its bounty. Traditional dishes like mirza ghasemi and baghala ghatogh are central to these feasts.

Provincial Adaptations of National Holidays

Iran’s national holidays, such as Nowruz and Yalda Night, often take on regional flavors, showcasing local customs:

- Isfahan’s Nowruz: Known for its elaborate flower displays and bustling bazaars, Isfahan adds a touch of architectural grandeur to the spring festivities.

- Khorasan’s Yalda Night: In Khorasan, Yalda is steeped in music, with performances of traditional dotar music and poetry recitations unique to the region.

- Lorestan’s Chaharshanbe Suri: In Lorestan, the festival includes equestrian games and competitions, reflecting the region’s tribal traditions.

Iran’s regional celebrations reflect the country’s extraordinary cultural mosaic. Each festival, whether rooted in ancient myths, seasonal cycles, or spiritual beliefs, offers a glimpse into the life and traditions of its people. Together, these regional festivities not only enrich Iran’s cultural heritage but also remind us of the beauty of diversity within unity.

Celebrations of Love and Fertility

Sepandarmazgan: Ancient Persian Valentine’s Day

Often referred to as the Persian Valentine’s Day, Sepandarmazgan is an ancient festival celebrating love, femininity, and the earth. Traditionally held on the 5th day of Esfand (late February), Sepandarmazgan honors Spandarmad, the Zoroastrian guardian angel of earth, fertility, and devotion.

Cultural Significance:

Honoring Women and Earth: In ancient Persia, women were celebrated as symbols of love, compassion, and creativity, akin to the earth’s nurturing role. Husbands presented their wives with gifts, while acts of kindness reinforced bonds within families.

Environmental Reverence: The festival underscored the sacredness of the earth, with prayers and rituals encouraging its preservation.

Parallels with Modern Customs:

Sepandarmazgan mirrors the contemporary observance of Valentine’s Day, emphasizing love and appreciation, but with a broader scope encompassing community unity and ecological respect.

Today, Iranians are reviving this celebration, aligning it with environmental awareness campaigns and gender appreciation events.

Conclusion

Iranian festivals are living bridges between ancient Persia and the modern world, preserving rituals that reflect timeless values while adapting to contemporary contexts. They serve as powerful tools of cultural diplomacy, inviting the global community to experience the richness of Iranian heritage.

By celebrating love, nature, and unity, these festivals transcend borders, fostering greater understanding and appreciation of a civilization that has profoundly influenced human history. Iranian festivals are not just events; they are a testament to the resilience of culture, offering insights into the enduring spirit of a nation and the beauty of humanity’s shared traditions.